Information Graphics: Charles Minard

Napoloeon’s invasion of Russia of 1812 was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars, as it had the effect of reducing the Grande Armée to a tiny fraction of it’s original strength.

Napoloeon’s invasion of Russia of 1812 was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars, as it had the effect of reducing the Grande Armée to a tiny fraction of it’s original strength.

This was not only an event of epic proportions it was also of momentous importance for European history, since it triggered a major shift in the balance of power in European politics, and signalled the end of French dominance in continental Europe.

This important historic event became the subject for many European painters who vividly contrasted the arrogance and hubris of the original invasion with the humiliation and the human suffering of the retreat from Moscow.

However, it was a French man, Charles Minard, in 1869, who had pioneeed the use of information graphics in engineering and statistics, who, decided to tell what had become a familiar story to most Europeans, in an a revolutionary new fashion.

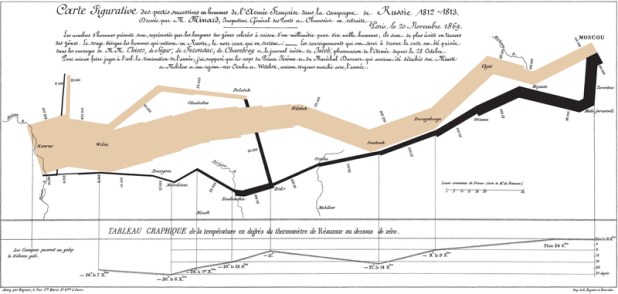

His “Carte Figurative des Pertes Successives en Hommes de l’Armée Française dans la Campagne de Russie 1812-1813”, is a flow map which portrays the losses suffered by Napoleon’s army in the Russian campaign of 1812. Beginning at the Polish-Russian border, the thick band shows the size of the army at each position. The path of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow in the bitterly cold winter is depicted by the dark lower band, which is tied to temperature and time scales.

This statistical graphic displays several variables in a single two-dimensional image. As it shows:

1) The Grande Armée’s location and direction, showing where particular units split off and rejoined

2) The declining size of the Grande Armée’s as it retreated back to France

3) The falling temperatures during the retreat.

Edward Tufte in his masterpiece “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” describes Charles Minard’s map as perhaps ” the best statistical graphic ever drawn”.

But it’s power is not just as piece of information graphics. Because although it might appear at first sight a colder, less emotional, less romantic depiction of the campaign, than the work of say Adolph Northen or Illarion Pryanishnikov it is, on closer inspection a far more chilling, and far more devastating depiction of the scale of the human folly and suffering.